*This piece was updated 6/30/2020 and was written in the loving memory of all the beloved souls who lost their lives in East St. Louis, July 2nd & 3rd, 1917. May you forever rest and power*

Today marks the 103rd anniversary of one of the most brutal episodes of mass violence in American history, but of course, most Americans don’t even know some shit like this even happened…

Before I hop into this history lesson I want to let you all know this piece hits close to home for me, and I mean that quite literally. Majority of my family is from the East Boogie (East St. Louis).

My grandparents on both sides of my family (like most black folks in America) are from the south and migrated to the midwest in hopes of escaping racial terrorism and economic prosperity.

My grandparents saw that hope in East St. Louis.

I spent most of my childhood in East St. Louis at my granddad’s house. Or as my cousin and I would say granddaddy house. For as long as I can remember, the east side was always the hood.

Seeing trap houses, PJ’s, and abandoned builds was an everyday thing for me growing up at my granddaddy’s house.

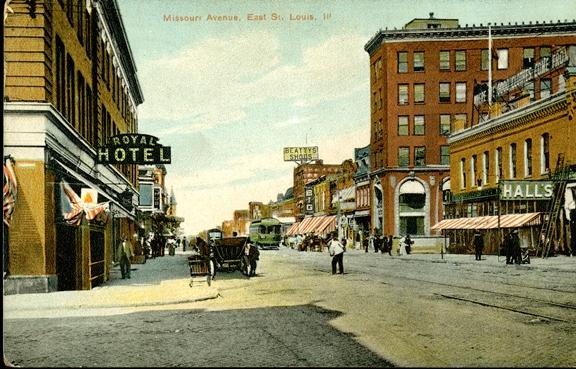

So you could imagine how shocked I was when I saw what the East Side looked like back in the day.

I was even more shocked when I found out the history that has been buried in the crumbling infrastructure of what once used to be a hub of industrial growth.

Illinoistown: The East Side I Never Knew

I know what your thinking… What the fuck is Illinoistown?

That’s what mfs USED to call East St. Louis. Anyway, after its incorporation in 1859, East St. Louis was home to only 5,600 people in 1870. Then came the National Stockyard in 1873 and the Eads Bridge one year later. The city became a tangle of 22 railroads connecting St. Louis to the north, east, and south.

By 1910, with 58,000 residents, the city was home to many industries that burned mountains of sooty coal from nearby Illinois mines. The big payrolls included Aluminum Ore Co., American Steel Foundry, Republic Iron & Steel, Obear Nester Glass, and Elliot Frog & Switch.

Many of the factories were built just beyond the city limit to avoid municipal taxes, which helped keep city services shoddy and corrupt. And also help underfund the community as a whole, but that’s a different story.

The adjoining town of National City was home to the stockyards and packing houses, including Armour and Swift. It handled nearly 5 million pigs annually and was the nation’s biggest market for horses and mules.

World War I created a bonanza for the draft-animal trade. Which made American’s industrial economy hum, but also created a unique situation.

High-demand in goods naturally calls for a high demand for able bodyworkers.

Earlier in this piece, I mentioned the fact that both my grandparents migrated from the south to escape racial terrorism and economic prosperity. This moment in American History is called The Great Migration.

For more info on the great migration and the racial terrorism that followed it, check out the first piece I published on TGA; “The Red Summer of 1919.”

Thousands of black people from the South moved north to work in war factories. East St. Louis’ black population, 6,000 strong in 1910, nearly doubled by 1917.

We have to remember the fact that black people at that time were in the middle of huge life transitions. Many men and women moved their entire families overnight with little to no money or savings. This, in turn, made it much easier for companies to hire and exploit these workers by demanding they work long hours for cheap wages.

In the Spring of 1917, the largely white workforce at Aluminum Ore, 32nd and Missouri avenues, went on strike. During the strike, Union leaders demanded that City Hall “get rid” of the newcomers.

How Shit Popped Off

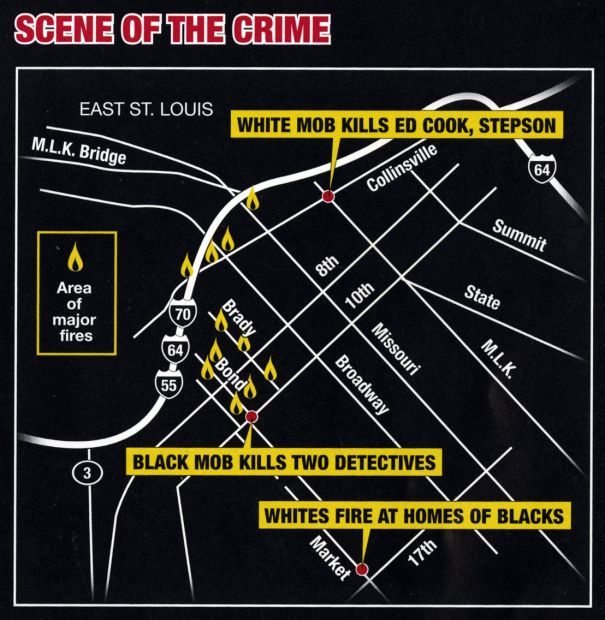

On the night of July 1st, 1917, a group of white men in a Ford, open fire into multiple black homes in downtown East St. Louis.

In the nature of self-defense and self-preservation, a group of black men got together and decided to, protect their hood if you will.

Once they were strapped up, they decided to gather on Bond Avenue and 10th Street and look for the mfs responsible for shooting up their neighborhood. Only knowing the perps were driving in a Ford during the shooting, they ended up opening fire on an oncoming Ford, killing two people who turned out to be police officers arriving to investigate.

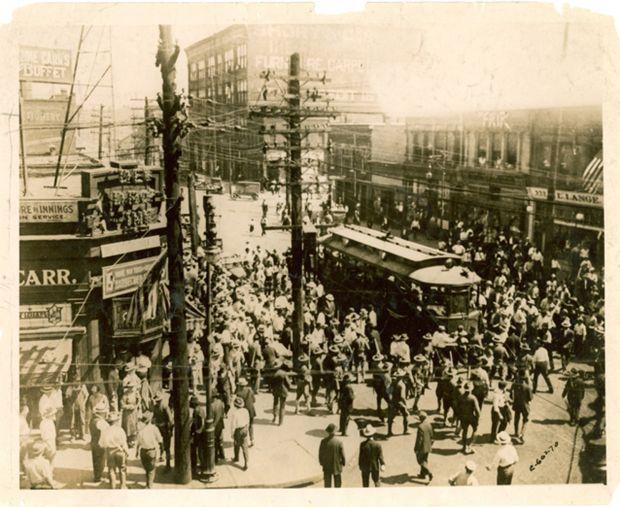

The next morning, whites poured from a tense meeting in the Labor Temple downtown and began unleashing violence this country has since tried to whitewash.

The East St. Louis Massacre

I was 23 years old (5 years ago) when I first about the East St. Louis Race Riot…

I was 23 years old (5 years ago) when I first about the East St. Louis Race Riot…

That’s right, I spent 23 years in an area that experienced one of the bloodiest massacres in American history yet I had not one damn clue it ever happened. Let alone, happened in my backyard.

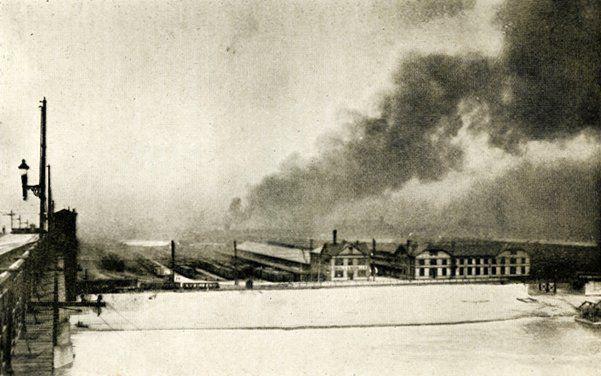

Rampaging white men used guns, rocks, pipes, and nooses. White women egged them on, sometimes taking part. Rioters set fires in black neighborhoods and torched the Broadway Opera House on the false tale that blacks were hiding there.

Many fled to St. Louis across the Eads and Municipal (MacArthur) bridges. East St. Louis police stood by or joined the carnage. Illinois National Guard soldiers who were hustled to town did little to protect people until late in the day.

More than 300 homes and businesses were burned. The local investigation was inept, so it’s hard to know the full scope of the carnage. The official death count was 39 blacks and nine whites, but the toll probably was anywhere between 100 – 300.

Factories begged black workers to return, but many didn’t. When schools reopened, black enrollment was down by more than half. A lengthy congressional investigation, reporting one year later, described the riot as “savagery.”

On July 3, the Post-Dispatch ran a harrowing account by Carlos F. Hurd. Since I believe this story is one that should never be forgotten, I’m not only going to link to his entire account about what he witnessed, I’m going to add it to the bottom of this piece.

“For an hour and a half last evening I saw the massacre of helpless negroes at Broadway and Fourth Street, in downtown East St. Louis, where black skin was a death warrant.

I saw man after man, with hands raised, pleading for his life, surrounded by groups of men — men who had never seen him before and knew nothing about him except that he was black — and saw them administer the ahistoric sentence of intolerance, death by stoning. I saw one of these men, almost dead from a savage shower of stones, hanged with a clothesline. Within a few paces of the pole from which he was suspended, four other negroes lay dead or dying, another having been removed, dead, a short time before. I saw the pockets of two of these negroes searched, without the finding of any weapon.”

– Post-Dispatch reporter Carlos Hurd’s eye-witness account of the East St. Louis race riot on July 2, 1917

#NeverForget

We’re often told to never forget the tragedies of the past. We’re told to never forget about the tragic actions that took place on 9/11. We’re told to never forget about the plight of the Jews and the dangers they faced under Nazi oppression.

But when it comes to the horrific past African Americans had to face in America mfs are quick to have amnesia.

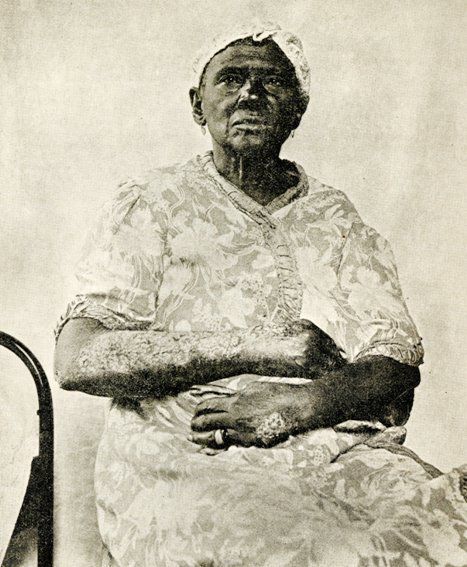

I want to end this piece by sharing images of the East St. Louis Race Riot of 1917. Let these images serve as a reminder of not only what back folks have endured in this country, but also what this country is capable of.

Post-Dispatch reporter Carlos Hurd’s eye-witness account

On July 3, the Post-Dispatch ran a harrowing account of the East St. Louis Race Riot by Carlos F. Hurd, the reporter who scooped the world with interviews of Titanic survivors five years before. Below is everything he saw and reported to the world. I encourage everyone to read it in its entirety in honor of all the lives lost to senseless hatred and racism. Warning! There are graphic acts of violence detailed in this passage.

“For an hour and a half last evening, I saw the massacre of helpless negroes at Broadway and Fourth Street, in downtown East St. Louis, where black skin was a death warrant.

I saw man after man, with hands raised, pleading for his life, surrounded by groups of men — men who had never seen him before and knew nothing about him except that he was black — and saw them administer the historic sentence of intolerance, death by stoning. I saw one of these men, almost dead from a savage shower of stones, hanged with a clothesline. Within a few paces of the pole from which he was suspended, four other negroes lay dead or dying, another having been removed, dead, a short time before. I saw the pockets of two of these negroes searched, without the finding of any weapon.

I saw one of these men, covered with blood and half-conscious, raise himself on his elbow and look feebly about, when a young man, standing directly behind him, lifted a flat stone in both hands and hurled it upon his neck. I saw negro women begging for mercy and pleading that they had harmed no one, set upon by white women of the baser sort, who laughed and answered the coarse sallies of men as they beat the negresses’ faces and breasts with fists, stones, and sticks. I saw one of these furies fling herself at a militiaman who was trying to protect a negress and wrestle with him for his bayonetted gun, while other women attacked the refugee.

Crowd mostly working men

A mob is passionate; a mob follows one man or a few men blindly; a mob sometimes takes chances. The East St. Louis affair, as I saw it, was a manhunt, conducted on a sporting basis, though with anything but the fair play which is the principle of sport. They went in small groups, there was little leadership, and there was a horribly cool deliberateness and a spirit of fun about it.

It was no crowd of hot-headed youths. Young men were in the greater number, but there were the middle-aged, no less active in the task of destroying the life of every discoverable black man. It was a shirt-sleeve gathering, and the men were mostly workingmen, except for some who had the aspect of mere loafers.

I would be more pessimistic about my fellow Americans than I am today if I could not say that there were other workingmen who protested against the senseless slaughter. Only a volley of lead would have stopped those murders. “Get a nigger, ” was the slogan, and it was varied by the recurrent cry, “Get another!” It was like nothing so much as the holiday crowd, with thumbs turned down in the Roman Coliseum, except that here the shouters were their own gladiators and their own wild beasts.

Fire drives out negroes

The sheds in the rear of negroes’ houses on Fourth Street had been ignited to drive out the negro occupants of the houses. And the slayers were waiting for them to come out.

It was stay in and be roasted, or come out and be slaughtered. A moment before I arrived, one negro had taken the desperate chance of coming out, and the rattle of revolver shots, which I heard as I approached the corner, was followed by the cry, “They’ve got him! …”

The firemen were at work on Broadway some distance east, but the flames immediately in the rear of the negro houses burned without hindrance.

A half-block to the south, there was a hue and cry at a railroad crossing, and a fusillade of shots was heard. More militiamen than I had seen elsewhere, up to that time, were standing on a platform and near a string of freight cars, and trying to keep back men who had started to pursue negroes along the track.

As I turned back toward Broadway, there was a shout at the alley and a negro ran out, apparently hoping to find protection. He paid no attention to missiles thrown from behind, none of which had hurt him much, but he was stopped in the middle of the street by a smashing blow in the jaw, struck by a man he had not seen.

‘Don’t do that,’ he appealed. ‘I haven’t hurt nobody.’ The answer was a blow from one side, a piece of curbstone from the other side, and a push that sent him on the brick pavement. He did not rise again, and the battering and kicking of his skull continued until he lay still, his blood flowing halfway across the street. Before he had been booted to the opposite curb, another negro appeared and the same deeds were repeated. …

The butchering of the fire-trapped negroes went on so rapidly that, when I walked back to the alley a few minutes later, one was lying dead in the alley on the west side of Fourth Street and another on the east side.

And now women began to appear. One frightened black girl, probably 20 years old, got as far as Broadway with no worse treatment than jeers and thrusts. At Broadway, in view of militiamen, the white women, several of whom had been watching the massacre of the negro men, pounced on the negroes. I do not wish to be understood as saying that those women were representative of the womanhood of East St. Louis. Their faces showed all too plainly exactly who and what they were. But they were the heroines of the moment with that gathering of men, and when one man, sick of the brutality he had seen, seized one of the women by the arm to stop an impending blow, he was hustled away with fists under his nose, and with more show of actual anger that had been bestowed on the negroes…

From negress-baiting, the well-pleased procession turned to see a lynching. A negro, his head laid open by a great stone-cut, had been dragged to the mouth of the alley on Fourth Street and a small rope was being put about his neck. There was a joking comment on the weakness of the rope. It broke, letting the negro tumble back to his knees.

An old man came out of his house to protest. ‘Don’t you hang that man on this street,’ he shouted. ‘I dare you to.’ He was pushed angrily away, and a rope, obviously strong enough for its purpose, was brought.

Right here I saw the most sickening incident of the evening. To put the rope around the negro’s neck, one of the lynchers stuck his fingers inside the gaping scalp and lifted the negro’s head by it, literally bathing his hand in the man’s blood. ‘Get hold, and pull for East St. Louis,’ called a man with a black coat and a new straw hat, as he seized the other end of the rope. The rope was long, but not too long for the number of hands that grasped it, and this time the negro was lifted to a height of about seven feet from the ground. The body was left hanging there.”

I had no idea. I have to believe there are many more Tulsas and Illinoistowns in this country’s history… Philly in 1985 came to mind as I read this too. Different, but similar underlying disregard for Black lives.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have you heard about the Wilmington insurrection of 1898?

LikeLike

I had not. However, as I was reading about it, my stomach knotted up because I have an overwhelming sense that massacres like these are not just a thing of the past.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Its not unfortunitaly…

LikeLike

Part of me is stunned I never learned of this (as a history major in college), but part of me is also not surprised. Nor was I aware of the Wilmington Insurrection of 1898 (which you mentioned above).

LikeLiked by 1 person